Castles of German Romanticism

In the 19th century, swept up in the fervour of national romanticism, Germany embraced a trend of building castles that were meant to evoke the heroic, chivalric past of the German people. Their architecture was consciously designed to align with the public’s image of medieval castles, much like those depicted in popular children’s fairy tales and light literature.

Whenever possible, these castles were strategically built on picturesque, rugged terrain – perched atop inaccessible hilltops, nestled in dense forests, or tucked along river bends. Funding came from Germany’s oldest and wealthiest noble families, who often chose sites where their ancestors had once held a modest castle or a sturdy ancestral home. Among the most notable of these romantic-era spendthrifts was the extravagant Bavarian King Ludwig II, who set a trend that other German aristocrats found hard to resist.

It must be admitted that these romantic castles (burgs) are genuine architectural masterpieces. Though catering to the immature tastes of their patrons and the nationalist fervour of the masses, the designers created buildings of intricate spatial and structural complexity, seamlessly blending them into their natural surroundings. Notably, when desired, they used all their expertise and the latest construction techniques to create an illusion of an authentic-looking half-ruin. Around the castle grounds, they would construct stable yet seemingly “half-crumbled” walls or deliberately insert structurally safe cracks into the castle walls, then treat them with the latest methods to look as aged and perilous as possible – all to give the impression that the castle was indeed several centuries old.

The most architecturally successful of these romanticized castles is Burg Hohenzollern. It was initially funded by the powerful Prussian ruling family, and later by German and Romanian ruling dynasties and designed by the Prussian court architect Friedrich August Stüler. To ensure authenticity, Stüler consulted the leading fortification engineer of his era.

Yet, despite the effort and expertise of their designers and all their construction skills, the fundamental flaw of these romanticized castles lies in their inherent inauthenticity, as their origins are orchestrated, contrived. Visitors to such a castle are fully aware that they are in a fabricated version of an idealized prototype, which makes it hard to immerse in in the faux-medieval ambiance.

But, does this mean the popular image of a medieval castle is just a romanticized fantasy? Surprisingly, not at all. The true embodiment of the idealized medieval castle, whose specific charm later romantic forgeries attempted to replicate, indeed exists. It is an authentic 12th-century castle hidden in a dense deciduous forest, about thirty kilometres from the city of Koblenz, and it is called Burg Eltz.

Burg Eltz – The Original of the Forgery

The valleys of the Rhine and Moselle rivers hold a special place in the enduring fascination with medieval castles. Interestingly, this “Rhine Romanticism” – a deep enchantment with the charm of the region’s ruined castles – first captured the imagination of England’s upper social circles and only later found its way to the German public. There, it became a precursor to the ill-fated German nationalist romanticism.

Burg Eltz is nestled in a pristine forest of untouched natural beauty, within the broader region of the Moselle River. The castle stands atop a 70-meter-high rock, around which the Eltzbach stream curves in a 180-degree arc, surrounding it with water on three sides. The only access is via a stone bridge leading to a gate that was easy to defend. In design, the castle roughly follows the elliptical shape of the rock on which it was built.

Burg Eltz, built in the 12th century, has a remarkable history of never being conquered or destroyed, remaining unscathed to this day. In the 19th century, it was owned by Count Karl zu Eltz, who undertook the inevitable reconstruction, but unlike many others, he refused to alter its appearance to suit contemporary tastes. Instead, he meticulously preserved its authenticity, which is a decision we highly commend from our modern perspective.

Throughout its existence, spanning 33 generations, Burg Eltz has remained in the hands of the Eltz family, one of the oldest families of the German high nobility, who are known to us as the rulers of Vukovar during the Habsburg era. The castle’s founder, Rudolfus Eltz, a loyal follower of Frederick Barbarossa, was granted the fiefdom and future castle site as a reward for his military service. His descendants split into three branches: Eltz Kempenich, Eltz Rübenach, and Eltz Rodendorf, which significantly influenced the castle’s internal organization.

These three families co-owned the castle but each built its residential wing of approximately equal size, alongside a shared communal area. Constructed and expanded over the course of several centuries, the castle had, by the late 15th century, grown to include around ten levels, spanning both above and below ground. Fans of 20th-century organic architecture might appreciate the ingenuity with which the subterranean rooms were integrated into the natural rock formations, which serve as walls.

The spontaneously constructed residential buildings of different families vary in storey heights, decorations, and architectural styles, resulting in a captivatingly vibrant overall impression. The limited space available at the foundations of each residential unit necessitated the construction of spiral staircases with unique, inventive exits at various levels. This is architecture born directly from the site itself – an organic design no architect could fully anticipate.

Castle Interior

The current owner of the castle, Dr Karl Graf von und zu Eltz-Kempenich, Faust von Stromberg, is a businessman living in Frankfurt. However, the residential section of the castle traditionally belonging to his Kempenich family branch is still used for the family’s living. The parts of the castle that previously belonged to the Rübenach and Rodendorf family branches are open to visitors. Recently, a group of tourists visited these sections, and our gracious hosts mentioned that it was the first group from Serbia to do so.

Overall, the castle boasts about eighty rooms, half of which have fireplaces. Many rooms, especially the bedrooms, have toilets that are automatically flushed – with rainwater – when it rains. On dry days, the flushing system is on hold; nevertheless, this was still a remarkable luxury by medieval European standards.

The residential areas of the castle have been modified and adapted over the centuries, a transformation that can be traced primarily through the furnishings, decorations, and room layouts. Generally, as visitors ascend to higher floors, they step into progressively more modern rooms. Climbing one floor is akin to travelling about one century closer to the present.

The Rübenach family’s living room dates back to the 14th century. It features a 15th-century Belgian tapestry and a painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder from the early Renaissance, a piece the hosts are particularly proud of. Above, the 15th-century room is adorned with floral murals from the time of its construction.

The kitchen, built in the 15th century, houses an array of authentic utensils ranging from the 15th to the 19th centuries. Its wall niches, significantly cooler than the rest of the kitchen, served as early refrigerators for storing food.

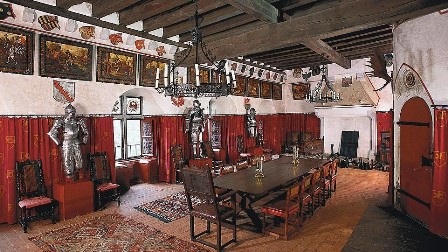

The interior of the Knight’s Hall, dating back to the 16th century and showcasing medieval knightly armour, exudes the wealth and power of the noble family, designed with the clear intent to impress guests. This was entirely fitting, as the room was used for negotiations with rivals. The decor, too, was purposefully chosen: masks of court jesters – the only individuals permitted to tell their lord unpleasant truths “in jest” – and “roses of silence,” a poignant reminder that nothing agreed upon in the room was to leave its walls. In this chamber of plots and intrigue, anything could be said, but what was spoken sub rosa had to remain inter nos. In the room dedicated to the elector princes of the Eltz family, visitors can admire Baroque and Rococo furniture from the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Hunting Room celebrated the pride of the castle’s men. It houses exquisite examples of antique rifles and hunting trophies from exotic lands: antlers of elk and deer, bear pelts, and stuffed heads of hunted animals, alongside fine pieces of carved solid wood furniture.

On the top floor, in one of the towers built in the picturesque timber-framing style, lies the countess’s reading and writing room, furnished with elegant 19th-century pieces.

“A Fairy-Tale Castle”

There is something truly extraordinary about the fate of Burg Eltz. While many other castles have, with varying success, conformed to the popular image of a fairy tale castle, this one seems to have taken the opposite path. Its construction predates not only that romanticized vision but even the concept of fairy tales themselves. Yet, when fairy tales gained popularity, the appearance of Burg Eltz played a crucial role in shaping how illustrators of children’s books, and eventually the broader public, came to imagine medieval knightly castles.

Today, it is widely accepted that the unintentional pioneer of this trend was the English painter J.M.W. Turner, who found in Burg Eltz a favoured motif. By a twist of history, this flamboyant English artist became a forerunner of both French Impressionism and German National Romanticism – two movements he could scarcely have imagined, as they blossomed long after his death. The first of these movements remains a crowning achievement of European civilization, while the second would drive that very civilization to the brink of destruction.

Darko Veselinović, July 2014