Case Study House Programme

In January 1945, with the end of the war in sight, the California-based magazine Art & Architecture, dedicated to modern art, design, and architecture, embarked on its most ambitious project yet: the Case Study House programme. With millions of American soldiers soon returning home, ready to build families – and homes – the magazine’s editorial team enlisted eight leading architects to design affordable, functional, modern houses. These homes were to be constructed using industrially manufactured components, making them easy to replicate on a large scale. The magazine planned to finance the construction of these houses, publish detailed accounts of their creation, and open them to the public for viewing.

The programme exceeded all expectations, continuing for the next 20 years. Instead of the originally planned eight designs, 36 were ultimately realised, most of which were built. Although this was not the original intention, the focus shifted to homes designed to suit the Southern California lifestyle. Most of the architects involved were based in Los Angeles, and nearly all the houses were built in its greater area. The contributors included luminaries such as Richard Neutra, Eero Saarinen, Charles Eames, Raphael Soriano, and other architectural icons of the era – true pillars of American Modernism.

More than half a century has passed since the zenith of the Case Study House programme, providing enough time to fully grasp the scale of its long-term cultural impact. From the very outset, the programme sparked immense interest, with the first six houses – completed in 1948 – drawing over 350,000 visitors. Yet, in a time before globalized media, the programme’s influence initially remained confined to the magazine’s readership and the Southern California residents who could visit the homes in person. Nevertheless, step by step, gradually but inexorably, the ideas fostered within the programme began to spread across the globe, propelled primarily by the power of photography and film.

Indirectly, the programme also achieved its primary goal: the mass production of these homes. This vision was realized by real-estate developer Joseph Eichler, who brought it to life adapting Raphael Soriano’s designs.

The Houses of the Programme

Of the 36 houses designed as part of the Case Study House programme and featured in Art & Architecture, 24 were constructed. Remarkably, only two have been demolished, four have undergone significant renovations, and the remaining 18 have preserved their original character, earning an iconic status. The numbering system introduced by the magazine continues to be used by enthusiasts even today, often paired with the name of the original owner – for example, Case Study House #9 (CSH#9), also known as the Estenza House.

While architects were given complete creative freedom, the programme’s objectives naturally guided them toward certain shared solutions. A typical Case Study house was single-storey with a flat roof, a steel-frame structure, and prefabricated walls and ceilings. The ceilings often featured exposed corrugated or trapezoidal steel sheets. Some walls were entirely glass, creating a seamless transition between interior and exterior spaces. When the surrounding environment allowed, dramatic natural elements were skilfully integrated into the interior design, bringing the outdoors in. The houses were also carefully adapted to the local microclimate conditions, with particular emphasis on mitigating summer heat, to avoid reliance on air conditioning.

For some architects involved in the programme, such as Richard Neutra, it was merely a chapter in a career already devoted to similar modernist principles. For others, the programme represented the pinnacle of their professional journey, steering them toward designing family homes in the California Modernism style and further developing ideas initiated during the project. For one participant, Pierre Koenig, the programme was more than just a milestone; it defined his entire life.

Pierre Koenig and the Pinnacle of the Programme

Although the Case Study House programme was never conceived as a competition, with no juries to evaluate the designs or readers casting votes, history has nevertheless recognized its winner. That distinction went to Pierre Koenig, a young architect from Los Angeles, who first encountered the programme as a draftsman for Raphael Soriano’s project. About a decade later, with considerable experience and a growing reputation, Koenig was personally invited by the magazine’s editors to create his own designs. In a relatively short period, he produced two designs, both of which were built and are now regarded as the crowning achievements of the entire programme.

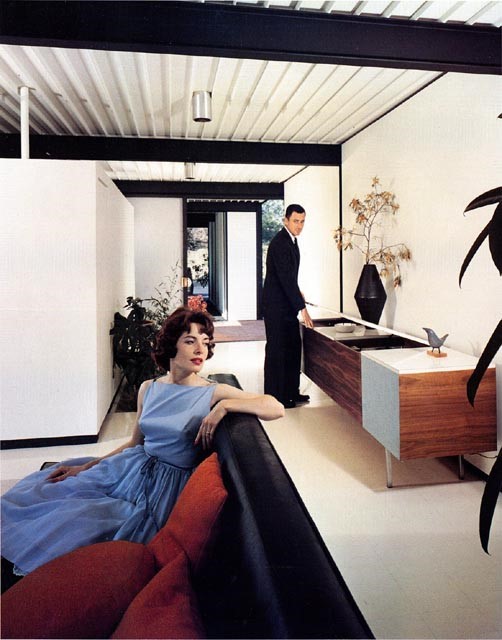

The first of these houses, Case Study House #21, constructed in 1959 and also known as the Bailey House, is considered the most faithful realization of the programme’s original objectives. It featured a steel frame, ceilings of exposed trapezoidal steel sheets, and walls made from industrially produced gypsum boards. The remarkable quality of the house design lies in its ability to create a glamorous home and lifestyle using such simple and inexpensive means. This was achieved through an ingenious adaptation of the house to blend seamlessly into its natural surroundings and microclimatic conditions. Such adaptability also meant that the design would need adjustments for each new location, but the foundational principles were firmly established. Following the success of this project, one could argue that the mission of Art & Architecture was fulfilled – every original goal of the programme was achieved.

Pierre Koenig, CSH#21, Bailey House, photo J. Shulman

However, then came Koenig’s second house, Case Study House #22, or the Stahl House, built in 1960, which represented an even more spectacular success. In terms of structure and production, it built upon the previous project, but it was constructed on a challenging hillside site where conventional building methods were not feasible. Koenig transformed the dramatic slope into the home’s greatest asset, creating a level of unprecedented glamour.

A pivotal role in promoting this house was played by Julius Shulman, the renowned architectural photographer, who at the time was working for Art & Architecture magazine. Shulman encountered this favourite project of his long career and never let it go. He photographed it from striking angles, day and night, at twilight, in sunlight and under clouds, both empty and alive with elegantly dressed ladies in the interior.

Wouldn’t you like to live in a house with exposed steel beams, gypsum-board walls, and a trapezoidal steel ceiling decking? Think again, because if there was ever a moment when the position of F.L. Wright’s Fallingwater was shaken from its pedestal as America’s most beloved house, it was when Shulman’s photographs of Koenig’s Stahl House appeared in Art & Architecture magazine.

The Global Success of California Modernism

The Case Study House programme was a key element in shaping the lifestyle that emerged in mid-20th-century California, ushering in an era of unprecedented relaxation, free-spiritedness, and glamour. The roots of the architectural style that defined the programme stretch back even earlier, before the war, with pioneers such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Rudolph Schindler, and Richard Neutra. In its developed form, this style took on various names, each with subtle differences in meaning, including American Modernism, Mid-century Modernism, and Organic Architecture, but it is most accurate to name it California Modernism.

California Modernism was characterized by simplicity, practicality, and a minimalist approach that stripped away anything superfluous – unless it was a part of a novel, glamorous experiment. Its glamour often arose from the seamless integration of the design with the rugged, untamed natural surroundings – the harsher, the better – or from the futuristic elements that emphasized the heroic, space-age era just on the horizon.

It’s noteworthy that not all of the era’s influential architects contributed to the Case Study House programme, and the reasons for their absence remain somewhat ambiguous. Frank Lloyd Wright was already advanced in years and lived outside of California, but his son, known simply as Lloyd Wright, was also a distinguished architect living and working in Los Angeles, and also opted not to participate. Rudolph Schindler, who passed away in 1953, missed the programme’s prime but could have contributed in its early stages. The most regrettable omission, however, was John Lautner – F.L. Wright’s student and collaborator, though far from a blind follower – who developed his own distinct style and designed some of the most extravagant buildings in Los Angeles. Perhaps he simply couldn’t conform to the programme’s demand for affordable construction?

As time passed, the structures of California Modernism have become source of inspiration for admirers worldwide. Koenig’s Stahl House and Lautner’s designs became iconic, frequently chosen as glamorous film locations, further cementing the movement’s legacy. A special mention goes to the photographer Julius Shulman, whose inventiveness not only flourished alongside the brilliance of California Modernism but helped immortalize it. Although Shulman reluctantly retired in protest against Postmodernism, refusing to endorse it, he made a temporary return to professional practice at the age of 95 to photograph the newly reconstructed Koenig’s Bailey House, remarking that no one else could do it as well as he could.

Darko Veselinović, March 2013