When the peoples of the Balkans began to break away from the Ottoman Empire and form their own nation-states, preserving the Ottoman architectural heritage was the last thing on their minds. Eager to modernize, the newly formed states embraced Central European cultural models, which lead to the demolition or neglect of public buildings from the Ottoman era, leaving them to decay.

However, the attitude towards residential buildings was somewhat different. For a while, the new elite continued to revel in the luxury of the oriental-style “konaks.” Within the broader initiative to develop national traditions, where “de-Ottomanization” played a pivotal role, the idea of a national house, supposedly unique to each nation, was promoted. Scholarly works described these as “traditional Macedonian houses,” “northern Greek houses,” or “houses of the Bulgarian Revival.” Yet, the distinctions among them were unconvincing, and their alleged connection to the national rural tradition remained rather vague. Over time, many autochthonous buildings deteriorated, replaced by the construction of traditional “ethno-villages” featuring konaks, chardaks, divanhanas, and hajduk huts of questionable authenticity.

In Albania, however, the circumstances were different. The national state was formed relatively late, and religious differences were not exploited. Additionally, the economic underdevelopment typical of the Balkans persisted longer, contributing to the preservation of old Balkan architecture for an extended period. This is especially true for two mythical, mountainous cities that have remained virtually untouched since Ottoman times and are now protected by UNESCO as World Cultural Heritage sites.

These cities are Berat and Gjirokastër.

Berat

Berat is an ancient city, known from the Middle Ages through the 17th-18th centuries by its Slavic name, Belgrad, which evolved into the name we know today. To set it apart from the more famous Belgrade, the Venetians called it Belgrado di Romania, while the Turks referred to it as Belgrad or Arnavud.

The city’s striking appearance first came to light through the accounts and illustrations of a few adventurous English travellers. Among them were C.R. Cockerell, an archaeologist, architect, and writer, and Edward Lear, a writer, painter, and composer, who has since become something of a local legend in Berat. In contrast, Lord Byron never managed to set foot in Berat. During his epic journey, the city’s ruler, Ibrahim Pasha, was at war with Byron’s host, Ali Pasha Tepelena, leaving the poet’s visit to Berat an unfulfilled aspiration. In the 18th and 19th centuries, residents of this mountain town built homes on the steep slopes overlooking the Osum River. These houses were packed closely together, with only narrow, winding, cobblestone alleyways and staircases snaking between them.

Berat 2020, Mangalam district

These striking Ottoman-Balkan houses, which have earned Berat its current renown, owe their enduring elegance to craftsmen-masons who worked carrying a single blueprint in their minds, and then adapting it to fit the real-life geometry of the terrain. Passed down through generations, from fathers or other skilled artisans, the design of these two-storey houses with an upper chardak evolved over time, with subtle modifications reflecting changing ways of life. The ground floor, built from stone and sometimes reinforced with wooden frames for additional earthquake resilience, had minimal openings. Primarily used for storage or sometimes housing animals, the space often contained little more than a staircase.

Berat 2020, a typical stairway-style thoroughfare

Family life took place on the upper floor, constructed with lighter wooden frames. While the architectural design evolved over time, its origins can be traced back to the traditional chardak – a term with varying meanings across regions, but in Albania, it primarily refers to a wooden veranda on the top floor. What began as an open-air space with simple coverings gradually transformed into enclosed space, and later into fully enclosed rooms, with majority of Berat homes typically featuring these wooden verandas – chardaks – framed by an array of large windows.

Berat 2020, National Ethnographic Museum, the interior of the enclosed section of the chardak

One of the largest traditional houses in the Mangalam district, the most attractive part of Berat, was built during the time when the transformation of the chardak was taking place. It is an excellent example of this architectural shift and was appropriately chosen to house the National Ethnographic Museum.

Religious buildings in Berat, despite their diversity, attract less attention than residential ones. In a country that officially embraced atheism, these buildings were not adequately maintained. Today, with funding from the Turkish government, some religious sites are being restored, including the modest mosque in the central square of Mangalam. If you venture towards the intriguing structure behind the mosque, the guard might stop you. But once you show that you recognize the dervish tekke, he sees you as a knowledgeable enthusiast and not only lets you in but also becomes a highly informative and even humorous guide. This tekke belonged to the Halveti Sufi dervish order. It is the most renowned tekke in Albania, a top-tier monument of culture, famous for its interior decoration and ceiling design, which is currently under reconstruction. There is a widespread belief among locals that Sabbatai Zevi, a 17th-century Kabbalist who was thought to be the messiah during his lifetime, is secretly buried in this tekke. There is no material evidence to confirm this, but it is documented that he corresponded with the Halveti dervishes of Berat before his death. Another tekke in Berat, situated on the outskirts of the city and architecturally unremarkable, belonged to the Rifai dervishes, known for their bizarre and occasionally terrifying rituals.

In addition to the equally represented Orthodox Christians and Muslims, the city was home to a significant Jewish community during Ottoman times, including crypto-Jews, whose symbols are still visible in the decorative elements on house facades and doors. During the Holocaust, Albania was the most successful European country in protecting its Jewish population. In this effort, nationalists, communists, and collaborationist authorities, otherwise fiercely opposed on all other issues, were united. Moreover, by the end of the war, Albania had a significantly larger Jewish population than at the outset, as endangered Jews from occupied Europe sought refuge there and were saved in the remote, hard-to-reach mountainous regions of the country, particularly in Berat.

For connoisseurs of traditional Balkan architecture, Berat is a must-see. However, a visit to Gjirokastër, another Albanian museum-town, is equally important, offering a chance to explore distinctively different Balkan house styles.

Gjirokastër Just like in Berat, the 18th and 19th centuries in Gjirokastër saw the rise of a wealthy class of citizens for whom skilled Macedonian stonemasons from the Debar region built ever-larger and more beautiful houses in the traditional style, reflecting the wealth and prestige of their owners. These houses, although evolved from the chardak-style houses, are distinct from those in Berat. While Berat houses typically have two floors, a typical home of a wealthy Gjirokastër family features three. The lower two floors are usually made of stone, sometimes brick, while the top floor, resulting from the transformation of the chardak, boasts a wooden framework, a row of large windows, and walls made using the wattle and daub technique. The large eaves often require support from rafters.

Gjirokastër 2020

While overhangs were a must-have in Berat, they were not favoured in Gjirokastër. The roofing in Berat features semi-circular ‘Turkish’ tiles, while Gjirokastër roofs are covered with rough stone shingles or natural slate, giving the city’s rooftops a distinctive grey hue.

The two lower floors of a house have high ceilings and reflect another famous Albanian tradition, characteristic of northern towns. These are the so-called towers, tall stone houses with small openings, adapted for armed defence and well-suited for unresolved blood feuds. While such features are occasionally found in Gjirokastër, where blood feuds were rare, the houses more often have large, beautifully crafted windows instead of small openings. Overall, the most striking houses in Gjirokastër, though typically rooted in the Oriental-Balkan style, often carry a subtle hint of Tuscan charm.

Gjirokastër 2020, a run-down town house displaying all the typical architectural features

Regardless of their architectural significance, both Berat and Gjirokastër hold a unique place in Albanian history. In fact, it could be said that their distinctive architecture reflects their position in the mountainous, hard-to-reach interior of the country, far from global influences, where, at least according to widespread belief, the mythical ideals of chivalry, the sworn word, and heroic ethics have been preserved.

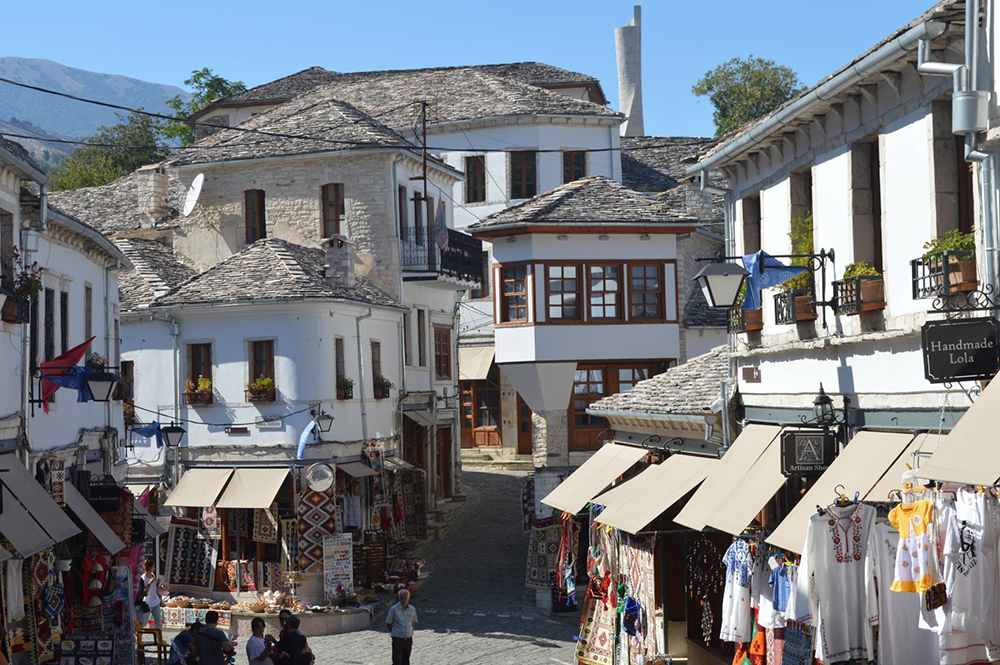

Gjirokastër 2020, Market Street in the city centre

In 1923, it was in Berat that the autocephalous Albanian Orthodox Church was founded, and in 1944, it was here that the partisan leader Enver Hoxha proclaimed a provisional government, marking the dawn of a new Albania.

Gjirokastër gave birth to two of the most famous Albanians of the twentieth century – Enver Hoxha and Ismail Kadare. They were born into similar Muslim bourgeois families with close ties to the dervishes of the Bektashi order. Yet, one would become a brutal dictator, while the other rose to fame as an acclaimed novelist. Today, the homes where they spent their childhood are open to visitors, with Hoxha’s childhood house even transformed into an Ethnographic Museum.

The relationship between these two figures remains enigmatic. In a country ruled by one of the harshest dictatorships, where any deviation from party lines was ruthlessly punished, Kadare wrote allegorical novels with themes carefully crafted to expose the dark paths of totalitarianism.

The reason why this was allowed remains a mystery. Hoxha’s regime was known for its ruthless handling and humiliation of rebellious writers. The young and talented Musine Kokalari spent eighteen years in prison and later was forced to sweep streets in a provincial town until she died in absolute poverty. The poet Sejfulla Malëshova endured twenty years in prison, after which he lived out his days as a warehouse labourer, never speaking another word, since no one dared to talk to him. At his funeral, only two agents of Sigurimi, the infamous secret police, were present. The official report for the archives: “He is truly dead,” signed by two barely legible signatures.

Kadare must have known all of this, or at least he could have known. And while some of his novels were occasionally banned, he personally faced no severe repercussions and even served as a member of the Parliament for a time. Did he manage to outsmart Hoxha’s censorship through clever metaphors, or did the wily dictator use him for political gain? Was there an unspoken arrangement, or did Kadare, an old fox, discover a soft spot in the dictator’s character – one who, despite his brutal reign, secretly harboured literary ambitions of his own?

There are some things we may never fully know. Balkan cities keep their secrets.

Darko Veselinović

December, 2020