The old quarter in Dubai

Today’s visitors to Dubai are undoubtedly dazzled by the city’s glamourous luxury. And there’s nothing wrong with that. But amidst the opulence, it’s easy to forget that just a few decades ago, this was a city of humble fishermen and pearl divers in the Persian Gulf. The city’s rapid and dramatic transformation left little room for preserving its architectural heritage. As a result, those in search of authentic remnants of old Dubai face a challenging, yet fortunately not impossible, task.

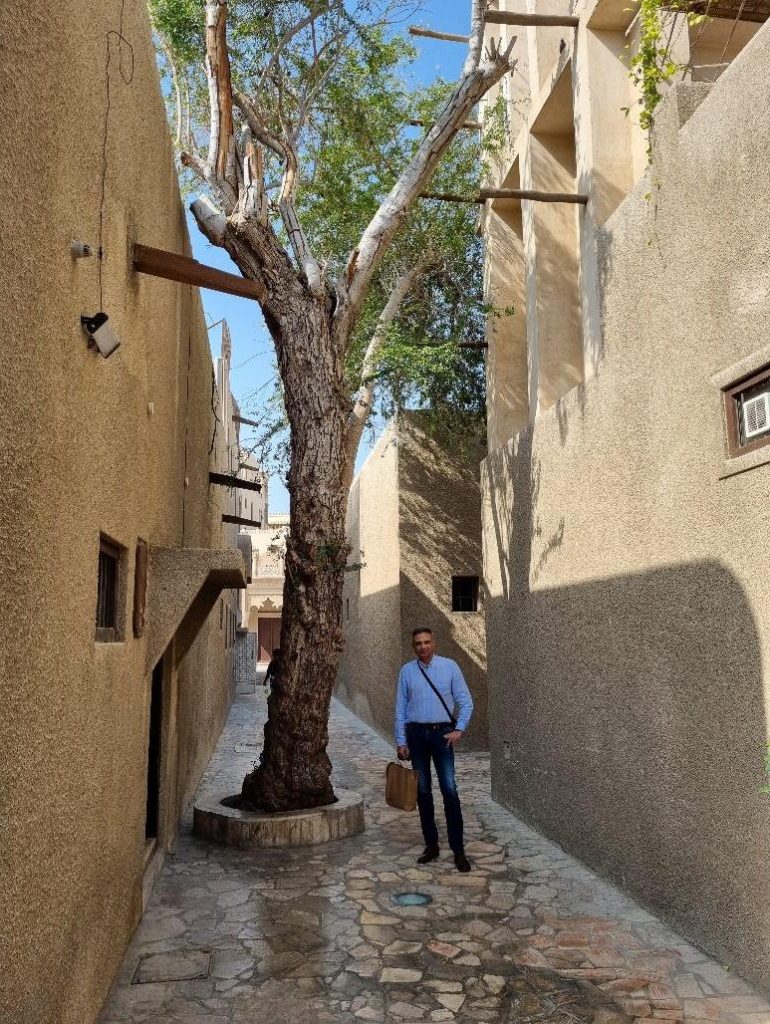

In a curious twist of fate, thanks to an unusual partnership between two classical architecture enthusiasts, a part of the city has retained its original character. Here, you can not only feel the spirit of old Dubai but also catch a glimpse of ancient Persia. This city quarter, historically known as Al Bastakiya, is now officially called the Al Fahidi Historical Neighbourhood. It lies north of most modern attractions, along the southern bank of Dubai Creek.

History of Al Bastakiya

The history of Al Bastakiya begins in the late 19th century when wealthy Persian merchants were enticed by the favourable conditions offered by the Emirate authorities, along with Dubai’s strategic geographic location. Drawn to these prospects, they settled in significant numbers along the banks of Dubai Creek, establishing sand-coloured houses nestled in narrow, winding streets that mirrored the cities in the Persian torrid zone. This new settlement, named Bastakiya after the southern Iranian town of Bastak, reflected the origins of some of the newly arrived Persian traders.

A century later, under vastly different circumstances of the 1980s, a portion of Al Bastakiya was demolished to make way for commercial buildings, and plans were already in motion to tear down the rest. The voice of opposition to such plans came from a British architect, Rayner Otter, who launched a campaign to preserve this historic part of the city. Yet, his efforts might have faltered if he hadn’t managed to attract a powerful ally – someone who understood architecture and whose opinion would hold weight with the ruling sheikh and his inner circle.

The ideal ally turned out to be Charles, Prince of Wales, the heir to the British throne. By that time, he had already gained a certain, albeit controversial, reputation in architectural circles for his persistent advocacy of classical architectural values, in line with his personal, elitist views. In this particular case, Prince Charles lived up to expectations and provided the crucial support needed to protect what remained of Al Bastakiya.

At the very entrance to Dubai’s historic quarter stands the must-visit Arabian Tea House – far more than just a place to enjoy Arabic tea. Set within a meticulously restored traditional townhouse, it offers a uniquely cosmopolitan ambiance where visitors from across the globe, each with their own distinctive flair and dress code, gather. Here, guests can indulge in dozens of tea and coffee options, alongside an array of authentic Arabic breakfast choices.

This popular tea house is one of many efforts to imbue the old quarter with a distinctly Arabic charm. However, its design unmistakably nods to Persian architectural traditions, reflecting its roots. For visitors, it’s the perfect chance to explore the marvels of one of history’s most intriguing engineering feats – the timeless legacy of ancient Persia.

Badgirs – Windcatchers

One of the most fascinating examples of ancient Persian engineering in the hot climate zones are the so-called badgirs, or windcatchers (bad = wind, gir = catcher). These towers, resembling church bell towers, rise above the rooftops, their peaks reaching higher layers where the wind is faster, cooler, and cleaner. The main concept was simple yet ingenious: the wind enters through openings at the top and is channelled down the tower, circulating through the central rooms of the house, bringing in a refreshing breeze and cooler air.

As is often the case in the Middle East, there is fierce rivalry over which civilization first invented windcatchers. While Egypt seems to have the earliest claim, with similar structures called malqaf, the Persian badgirs, with their superior design and versatility, eventually outshone their Arab counterparts. It is believed that the development of Persian windcatchers began during the golden age of the Persian Empire, around the 6th century BCE. Over the following centuries, their distinctive appearance became a defining feature of the skylines in Iran’s desert cities, especially Yazd, a city also known for its large Zoroastrian community.

In Persian cities, windcatchers were primarily built from mud, as in Yazd, or from sun-dried bricks. A key structural element was the inclusion of horizontal wooden poles, which provided stability but were primarily used as scaffolding for the frequent repairs that mud structures required, especially in the Sahara and Sahel regions. Over time, these wooden elements took on a decorative role, as is certainly the case with the windcatchers in Dubai.

As the centuries went by, ancient Persian engineers continued to raise their windcatchers higher, studying airflow patterns, overcoming challenges, and coming up with new, creative uses for their designs. Some of the windcatchers were even turned to face against the wind, allowing air to exit through them and creating a negative air pressure inside the house. Often, they were built in pairs (one to bring in air and the other to let it out) or as dual-function systems that both intake and exhaust air. In the absence of wind, badgirs functioned like chimneys, drawing warm air out. Initially, the openings were positioned to face the prevailing wind direction, but later designs featured openings on all four sides, with the option to close some of them and direct airflow through multiple separate vertical channels, depending on the desired outcome and wind direction.

Not only did windcatchers serve as ancient air conditioning systems, but they were also multifunctional and could be controlled.

The most innovative use of badgirs was in combination with another brilliant piece of Persian engineering – the qanats. A Persian qanat is an underground water channel that carries water on a gentle incline from the source to the city’s reservoir, similar to Roman aqueducts but entirely underground. Material evidence indicates that Persia was the birthplace of this technical invention, although it became widespread in the Arab world, continuing the long-standing rivalry between Arabs and Persians over the origins, which has persisted even in this case. Actually, the very term “qanat” comes from the Arabic language, while in Iran, the term “kariz” is also used, particularly for more complex and branched underground aqueduct systems.

Qanats were sometimes connected to the homes of wealthier families. When exhaust windcatchers, facing away from the wind, created a negative pressure inside the house, fresh air would enter from the qanat, gliding over the surface of the water. Due to water evaporation, the air was cooled even further before entering the house. Ladies and gentlemen, this was more than simple ventilation – this was air conditioning.

Additionally, because desert temperatures drop significantly at night, cold night air would enter the qanats and water reservoirs through vertical shafts, remaining trapped and cool until the low pressure generated by the wind catchers would draw it into the house. Not only did the ancient Persians cool their homes this way, but they also managed to keep water supplies in public reservoirs at near-zero temperatures well into the summer months – all without using electricity or fossil fuels, relying solely on the energy of the sun and wind.

Now that our understanding of thermodynamics and fluid mechanics has greatly advanced since the time of the ancient Persian builders, we believe that the use of windcatchers can be made even more efficient, providing a viable alternative to modern electric air conditioners, which are slowly destroying our planet.

Windcatchers in Today’s Dubai

Windcatchers are an architectural hallmark cherished by both Arabs and Persians, often featured in modern buildings throughout the sweltering cities of the Middle East. In some cases, they serve as genuine “green air conditioners,” while in others, they act as decorative nods to tradition.

The authentic Persian badgirs can be found in Al Bastakiya, but you’ll also spot them all over the city, sometimes in surprising places – ranging from modest quarters inhabited by hardworking Indian and Pakistani laborers to the opulent villas, where wind catchers are purely ornamental, showcasing the wealthy owners’ respect for the region’s architectural legacy.

Darko Veselinović, June 2022.