The Social Context of the Project

Italy in the 16th century was an exhilarating place to live. The Renaissance had unleashed the full splendour of human intellectual potential, and the ideal of the Renaissance man – one for whom intellectual limits did not exist – took shape. The Renaissance elites eagerly explored human anatomy, the functioning of internal organs and the arrangement of muscles, channelling this newfound knowledge to sculpt realistic, often sensual human figures from stone. For the first time in history, painters mastered perspective and played with it. The true movements of the planets were no longer shrouded in mystery, and the concept of an infinite universe redefined humanity’s place within it. They invented new games, competed in mathematical problems, used negative and complex numbers, and even gambled out of sheer curiosity to better understand the laws of probability. Within a span of a single generation, the culture of the classical world was not only reached but ultimately surpassed.

However, a dark shadow loomed over this vibrant world. The Ottoman Empire, led by Sultan Suleiman and Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, was the most powerful military force in the world at the time. There were growing fears that Italy might become its next victim in the course of expansion. The Republic of Venice was especially vulnerable, having already lost some of its overseas possessions to the Ottomans, with the loss of Cyprus being particularly devastating.

In the struggle for survival, the brief reprieve secured by the victory at the Battle of Lepanto, on 7 October 1571, had to be wisely utilized. The authorities of the Republic decided to build a city with an impregnable fortress at a strategic location near Trieste, along the route to Venice. Officially, it was to defend against the Ottomans advancing from Bosnia, but unofficially, it also served as a safeguard against the looming threat of the Habsburg Empire. The city would be named Palmanova, and the execution of this ambitious plan was entrusted to Marcantonio Barbaro, the Republic’s most capable statesman at the time.

Construction organiser – Marcantionio Barbaro

Marcantonio Barbaro was born into one of the wealthiest and most influential families of Venetian aristocracy during the zenith of the Italian Renaissance. The cultural stimuli he encountered in his youth shaped his view of the world for the rest of his life. Apart from being known as an amateur sculptor, Barbaro also served for a time as a rector of the University of Padua during the tenure of a young professor named Galileo. However, his greatest accomplishments lay in diplomacy and peace negotiations following decisive battles against the Ottomans. His success in this arena was greatly aided by mutual respect and a personal friendship with Solomon Ashkenazi, the chief negotiator on the opposing Ottoman side.

Marcantonio Barbaro was a connoisseur and admirer of architecture. When he and his brother Daniel set out to build their family villa, they commissioned none other than Andrea Palladio, the most influential architectural theorist and a devoted follower of classical art. The brothers themselves contributed to the villa’s design, particularly Daniel, who was also an architectural theorist. Their home, Villa Barbaro, is today recognized as a World Heritage Site. As long as Palladio was alive, Marcantonio Barbaro used his influence to secure prominent state projects for the architect. After Palladio’s death, Barbaro championed Vincenzo Scamozzi as his successor, who successfully completed many of Palladio’s unfinished works.

City Planning

In planning Palmanova, Marcantonio Barbaro’s primary task was to create an impregnable fortress. However, he also harboured a more personal, secret ambition: to seize this opportunity to bring a typical Renaissance vision to life. He aspired to create an ideal, utopian city.

The flood of ideas about an ideal society had been sparked by Thomas More’s Utopia, which soon inspired other thinkers to delve into this intriguing social-philosophical terrain. Most of them advocated for the equality of citizens, while concepts of religious relativism and theocratic governance competed with each other.

By the time Palmanova’s construction was in full swing, Tommaso Campanella added the finishing touch. From prison, he published The City of the Sun, presenting a new vision of an ideal theocratic communist utopia where all property was communal, and people worked just four hours a day. In his utopian city, even women and children would be shared. Love would be separated from sex, which would be regulated and planned at the community level with the aim of breeding the highest-quality offspring for the human race. Intriguing ideas, aren’t they? No wonder his imprisonment was extended, to a total of 27 years.

In any case, debates and polemics on the topic of the ideal society were not lacking, and thus, towards the end of the 16th century, Marcantonio Barbaro found himself with the rare chance to bring a Renaissance utopian dream into reality.

Various sources offer differing accounts of whom Barbaro enlisted as the chief designer of Palmanova. Some point to his favoured architect, Vincenzo Scamozzi, while others suggest the involvement of fortification expert Giulio Savorgnan. However, it seems likely that both were engaged, each handling their respective part of the work.

After meticulous preparations, the foundation stone for the construction of the ideal city was ceremoniously laid on 7 October 1593, marking the 22nd anniversary of the Battle of Lepanto. This date was chosen to once again underscore the fateful importance of this project.

Defensive function

Giulio Savorgnan was the world’s foremost expert in fortress construction at the time, and he brought not only his vast experience but also the latest fortification innovations to the building of Palmanova. Today, Palmanova is regarded as the best example of an Italian-style fortress, whose development is credited not only to Savorgnan but also to many of his predecessors, including Michelangelo himself. The foundational concept of the Italian fortress, trace italienne, was so well-developed that the next generation of military engineers, the most renowned of whom was the French engineer Vauban, had little left to add.

There is no better example of trace italienne than Palmanova. Enthusiasts and connoisseurs of fortification architecture can witness all the essential defensive elements there. Palmanova boasts nine arrow-shaped bastions connected by ramparts – curtain walls, three entrance gates, a water-filled moat, a secondary ring of bastions, ravelins, fausse-brayes, and other fortification elements whose names are now familiar only to experts. At Palmanova’s central square, an open-air exhibition showcases the engineering techniques used to construct such fortresses, as described by one of Savorgnan’s collaborators, Bonaiuto Lorini, in his treatise Delle fortificationi. The famous Galileo also documented the construction of Palmanova in one of his works.

The fortress was never taken by military force, though it changed hands several times as a result of peace negotiations. In the early 19th century, it came under the control of Napoleon’s forces, who gave it its final form by adding several defensive elements.

The Ideal City

Giulio Savorgnan completed his part of the work perfectly, utilizing the well-established knowledge, but Vincenzo Scamozzi faced the toughest task an architect could undertake: to create an ideal city within the fortress walls, where life would be perfect. He had to start somewhere, but all he had were speculative musings of writers – people with no practical experience, and no prior concrete attempts to draw upon. The most concrete reference came from 15th-century Florentine-Milanese architect Filarete, who in his theoretical work, described and illustrated his vision of an ideal city with a few drawings.

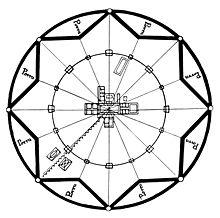

Filarete’s ideal city, Sforzinda, was envisioned as an octagonal star inscribed within a circle, featuring eight towers and eight gates. The streets were arranged radially, with every other street being a canal for transporting goods by water, and a connection to a river outside the city was also to be included. Although Filarete’s understanding of defensive functions was quickly outdated, and he was personally influenced by astrology and occult teachings, his work nonetheless sparked interest and professional responses. Inspired by his ideas, other Italian Renaissance engineers, including the renowned Leonardo da Vinci, put their visions of ideal cities to paper.

This may have influenced Scamozzi, who adopted a radial and concentric polygonal street layout in Palmanova. The city featured houses on roughly equal plots of land, reflecting the principles of citizen equality. At the centre of the city lies a large square with a cathedral and public buildings. The cathedral, the Duomo, was designed with a very low bell tower to prevent it from being seen by enemies outside the walls, thus making their orientation more difficult. The square was once adorned with statues of former mayors, known as provveditori, positioned at the beginning of each radial street. However, this tradition was abandoned at the end of the 17th century, and even the mayors’ names were erased – perhaps in the name of the proclaimed equality among citizens.

Shortly after construction began, both the chief political organizer, Marcantonio Barbaro, and the principal fortification engineer, Giulio Savorgnan, passed away. This left Vincenzo Scamozzi as the sole original visionary working on the realization of the ideal city. It was an impossible mission.

Despite the considerable efforts, the city failed to meet expectations. No one wanted to live there. Something essential was missing, though it was difficult to pinpoint exactly what it was. The historical records indicate that the Republic’s authorities made several attempts to motivate people to settle there. They offered free land plots and building materials, and even released prisoners on the condition that they settle in the city, but all these efforts had almost no success. Four centuries later, the situation is hardly better. The city is, of course, not deserted – people do live there – but it lacks the charm and vibrancy of other Italian cities.

Palmanova stands as the first, most comprehensive, and most ambitious attempt to create an ideal city. Later projects of a similar nature, sometimes initiated by humanist circles and other times by totalitarian regimes, were more modest in their goals and better aligned with real-world needs.

As part of a broader initiative, Palmanova has been protected by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, recognizing its historical and cultural significance.

Darko Veselinović, May 2023