Arrival in Shanghai

László Ede Hugyecz was born in 1893 in Banska Bystrica, a Slovak town that was then part of the Kingdom of Hungary. His father, György Hugyecz, a Hungarianized Slovak, was a wealthy and accomplished architect who ensured his children enjoyed an idyllic upbringing. Family travels broadened their horizons, and at home, they spoke Hungarian, Slovak, and German.

László studied architecture at the University of Budapest, earned his degree and immediately received job offers from contemporary legends like the art historian Ybl Ervin and the steel structure designer Virgil Nagy. Unfortunately, he soon received another call that couldn’t be ignored – from the conscription office. The Great War had begun, and his life took an unexpected turn. Drafted into the army, László was wounded on the Russian front and captured by the Cossack cavalry. In the confines of a prisoner-of-war camp, his architectural expertise didn’t go unnoticed – he contributed to construction projects while also learning Russian, until an opportunity knocked: he escaped from a stranded prisoner train in Siberia. Armed with a forged Cyrillic passport and fluent Russian, he managed to reach the Chinese border and from there, the cosmopolitan city of Shanghai.

There, he was utterly mesmerized – the city was dazzling.

Interwar Shanghai

At the time, Shanghai had a special legal status, and its core consisted of the so-called “concessions,” free-trade zones designated for foreign entrepreneurs. Adjacent to the old Chinese city, the French Concession was established, followed by the British to the north, then the American. When the Italians, Germans, and Japanese joined, the result was an unparalleled cosmopolitan entrepreneurial atmosphere, like nowhere else in the world. In this liberal environment, the economy thrived, along with gambling, prostitution, and the opium trade, whose steady supply was diligently orchestrated by the Green Gang, a local Chinese mafia. All the free-spirited ideas of the world, along with its every vice – unchecked and readily accessible – converged in this city of oriental mystique, adventure, and glamour.

This liberal, cosmopolitan allure reached its peak after the Great War, with the influx of defeated “White” Russians, who brought a highbrow, aristocratic culture to Shanghai’s enclaves of foreigners. Soon after, persecuted European Jews arrived, infusing the city with their unmatched entrepreneurial spirit. Particularly noteworthy was the influence of Russian noblewomen who elevated the already high standards of service in Shanghai’s brothels to unprecedented levels.

“There never was and never will be another city like Shanghai between the wars. It is a mix of Western and Oriental character, a city of stark contrasts. This Oriental Paris, with all its good and evil, has proved to be a paradise for adventurers,” reflected Elly Kadoorie, himself one of such adventurers, a Baghdadi Jew who made his fortune in interwar Shanghai.

In the unholy trinity of sin-cities of the era – Paris, Berlin, and Shanghai – the latter established itself as the most daring and thrilling, owing to its unparalleled freedom and diversity. Entrepreneurs, spies, gamblers, and musicians flocked to Shanghai from every corner of the globe. The local Chinese population, blending with foreign newcomers, eagerly embraced new skills, adding an authentic Oriental charm to everything. When an African American opened Shanghai’s first jazz club, the Carlton Café, and brought in eccentric American musicians, their Chinese counterparts, who had never encountered such music before, initially struggled to emulate the Black performers. Over time, however, they grew more confident and began contributing their own creative twists. Among the notable figures was composer Li Jinhui, who single-handedly developed “yellow jazz,” a pornographic musical genre that became highly popular in Shanghai at the time.

Interwar Architecture in Shanghai

In the dynamic atmosphere of interwar Shanghai, construction flourished, and architects were held in high regard. While the Chinese districts adhered to traditional Oriental designs, with their characteristic concave roofs, the foreign concessions embraced primarily Western architecture, where Oriental motifs appeared sporadically as accompanying eclectic elements. Buildings reminiscent of Europe’s most beautiful cities sprang up, showcasing neo-Romanesque, neo-Gothic, neo-Renaissance, and neo-Baroque styles side by side. However, Art Deco eventually emerged as the dominant architectural trend.

While much of the city’s ordinary population lived in shikumen – distinctive Shanghai terraced houses – the elite, both Western and Chinese, erected grand residences surrounded by gardens. They also established exclusive clubs, serving as venues for opulent and uninhibited nocturnal festivities.

Naturally, in a city where everything was permitted, architecture was anything but conventional. Favoured designs incorporated Spanish, Italian, English, Islamic, and classical motifs – often blended together – with a touch of Chinese ornamentation. Initially, only architects from Europe and America were commissioned for projects. However, a new generation of Chinese architects gradually emerged, mastering Western architectural styles not in formal classrooms but through practical, hands-on experience on site. The private residence of Swedish shipping magnate Eric Moller, designed to evoke the feel of a European medieval castle, was constructed in a style the Chinese called “Norwegian.” According to legend, Moller’s daughter fell asleep after reading Andersen’s fairy tales and dreamt of a magical castle where she longed to live. She woke up and quickly, before the image faded, sketched the castle, and her doting father enlisted an architect who turned her dream into reality. The villa later became infamous for its association with Shanghai authorities and less-than-pleasant activities, serving as the headquarters for Chiang Kai-shek’s intelligence services, then as the base for a communist youth organization, and later, a detention centre for corruption suspects. Many years later, Moller’s daughter, somewhat reluctantly, debunked the legend about her dream-inspired sketch. Today, the villa operates as a hotel, a fitting use given its expansive size with over 100 rooms, where Moller’s many pets once lounged.

Later, when a residential building was constructed beside the villa, the Chinese architect who designed it was aware of the proximity of such an iconic structure, and knew it would have some influence on his design. Unsure of how to approach this challenge, he opted to create stylized towers to mirror those on Moller’s villa. However, he only succeeded in creating a visual chaos. But then again, this is Shanghai. When such uncertainty first arises, we might call it a mistake, but when it becomes a recurring feature, we say it contributes to the vibrant character of the city.

László Hudec in Shanghai

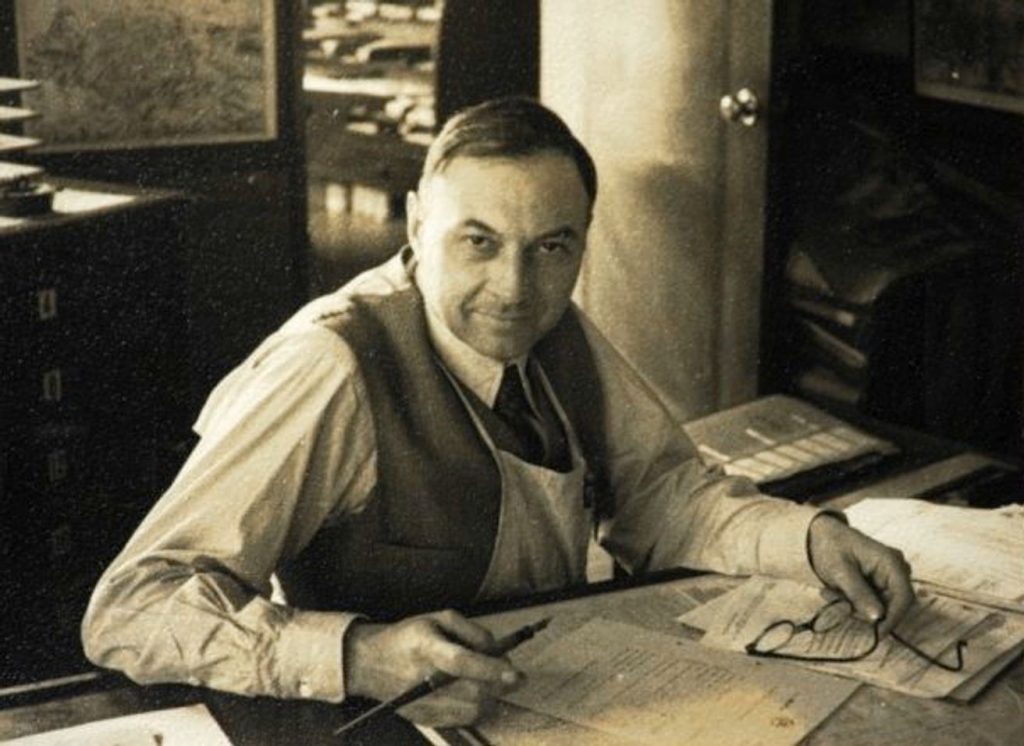

In this lively atmosphere, young architect László Hugyecz quickly found his way. When his forged Russian Cyrillic passport was transliterated into a Latin-script Czechoslovak passport, the Slovak form of his surname, Hudec, was recorded. He would carry this form of his surname for the rest of his life. Meanwhile, his family, having lost everything amid the chaos of war and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, struggled to survive in Budapest. Under such circumstances, returning to his homeland seemed utterly pointless.

Within just a few years, he became the most successful architect in the city, earning an undisputed status as the “famous Hungarian architect” that endures to this day. He founded his own firm, simply named “LE Hudec.” It’s fascinating to note that Mr Hudec spoke nine European languages and, to a certain extent, Chinese, which paints a vivid picture of daily life in this cosmopolitan megalopolis. Given that he spent his entire career in Shanghai, it remains unclear whether architectural circles in Slovakia and Hungary are even aware of his legacy. However, this dilemma might be seen in context: Shanghai is approximately twice the size of Hungary and Slovakia combined, and the difference in urban development is so vast that comparisons hardly seem fair.

In addition to the wealthy Westerners, a class of affluent Chinese also rose in Shanghai. Mr Hudec, known to them as Wu Dake, became their favourite architect. This was partly because, as a Czechoslovak citizen, he was subject to Chinese laws, given that Czechoslovakia did not have its own concession in Shanghai. Among Hudec’s most cherished clients was the wealthy industrialist Liu Jisheng, who was said to be endlessly in love with his wife. For her 40th birthday, he decided to gift her a garden to complement their elegant neoclassical villa, another Hudec’s works. Liu, of course, commissioned Hudec to design a garden. Moved by the couple’s love and devotion, Hudec found inspiration in the classical myth of Psyche and Cupid. Moreover, he ordered a statue of Psyche from Italy and placed it on a fountain in the garden as his personal gift to the Liu couple. It was believed that Hudec drew inspiration for the garden’s main motifs from “The Bath of Psyche,” a painting by the English neoclassical artist Frederick Leighton. Today, the villa serves as the headquarters of the Writers’ Association, and the statue of Psyche is still there, having survived the Cultural Revolution by being temporarily hidden, thus saving it from almost certain destruction.

The two most striking landmarks of interwar Shanghai were the Park Hotel Shanghai and the Shanghai Race Club clubhouse, both completed in 1934 and situated practically across from each other.

The Park Hotel Shanghai, designed under the influence of New York’s American Radiator Building, stands as László Hudec’s masterpiece and an epitome of mature Art Deco. With its 22 above-ground and 2 underground floors, it was the first skyscraper in Asia and remained the tallest building on the continent for several decades. In the turbulent times that followed, the hotel’s “bourgeois” interior underwent significant changes. However, in the early 2000s, a group of American designers restored its Art Deco look.

Just behind the Park Hotel, directly connected to it, stands the magnificent Grand Theatre, an Art Deco gem by László Hudec completed in 1933. This cinema, boasting over 1,500 seats, was cutting-edge for its time, equipped with translation devices at every seat to allow Chinese audiences to follow foreign films.

Across from the Park Hotel lies the Shanghai Race Club clubhouse, so the two buildings face each other with their main façades. One of the favourite pastimes for foreigners in the city was horse racing, which was also one of the most lucrative business activities. The city’s elite often owned racing stables and even competed as skilled jockeys. Among the fiercest competitors on the racetrack were Hudec’s colleague, Scottish architect Eric Cumine, and the shipping magnate Eric Moller, the owner of the previously described “Norwegian” villa with over 100 rooms.

The unique urban atmosphere of interwar Shanghai flourished until the Japanese invasion in 1938, which resulted in the occupation of the Chinese part of the city. Three years later, just a day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan also took control of the International Settlement, and the French Concession, effectively halting any significant commercial or artistic activity in the city. By that time, with Czechoslovakia already dissolved by the Nazis, László Hudec had applied for and received Hungarian citizenship. He even served as the honorary Hungarian consul in Shanghai.

However, the final blow to the city’s cosmopolitan spirit came with Maoist communist control. Most foreigners fled, and those who remained were labelled as class enemies, facing bleak prospects for survival. Among them was Hudec, who once again demonstrated his resourcefulness, much like when he had escaped from a Siberian camp with a forged passport in his youth. He successfully bribed his captors and, with a few suitcases in hand, made his way first to Switzerland and then to San Francisco. There, he taught at the University of California, Berkeley, but never returned to architectural design.

Today, Hudec is a legend in Shanghai. His work is highly regarded, and nearly all of his preserved buildings have been officially designated as “significant Shanghai historical monuments.”

Darko Veselinović