Ankara – Atatürk’s City

In the aftermath of the Great War, the final act of the Ottoman Empire’s disintegration was set in motion. Once the world’s most powerful empire, it now faced relentless territorial dismemberment. The complete collapse was averted by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s republican army, which successfully stood against the rule of the sultan, foreign occupiers, and Greek insurgents.

Yet, winning a war was one thing; confronting the dire backwardness of the country inherited from the Ottoman sultans was quite another. It was necessary to start anew, and Atatürk launched a program of sweeping reforms that turned people’s lives upside down. Yesterday’s subjects of the sultan were stripped of their turbans, fezzes, hijabs, and dervish orders and Sharia law were abolished. In their place came surnames, voting rights, and a Swiss-inspired civil code. A language reform introduced the Latin alphabet, and a nationwide education initiative followed. Atatürk himself authored a geometry textbook just to make sure no errors slipped through.

While the wealthy, cosmopolitan cities of western Turkey remained under foreign occupation, Atatürk declared Ankara, a remote Anatolian town, the capital of the emerging Republic. The success of these fundamental social reforms is most vividly evident today on the streets of this city, which has become a vibrant showcase of a new, proud Turkey. The once-isolated town, a provincial backwater, has transformed into a global metropolis, with its population soaring from thirty thousand to about five million. The winding alleys have given way to wide boulevards, and humble corner shops have grown into endless rows of luxurious office buildings, car showrooms, and shopping malls.

The First National Architectural Movement

At the dawn of Turkey’s transformative era, a small group of architects was poised to seize the opportunity to offer the new government an already-developed, ready-made stylistic solution tailored to fit the ideals of national revival. By the time the Republic was established, the creation of this distinctive style had been underway for at least 10–15 years, significantly shaped by political turmoil. As Christian nations, and later Muslim ones, began breaking away from the Ottoman Empire, Turkish architecture found itself in a state of constant self-reinvention. In its final form, it came to reflect primarily Turkish, rather than pan-Islamic or supranational “Ottoman” values. Furthermore, it sought to distance itself from classical Ottoman architecture, now deemed reactionary. Looking to emulate the success of Western nations, it emphasized modern trends without succumbing to slavish imitation. Despite these ideological challenges, a handful of Turkish architects skilfully navigated between the Scylla and Charybdis of tradition and modernity. They produced Western-style structures adorned with Oriental motifs, conveying a distinctly national yet non-Islamic character. Contemporaries referred to their work as the Neo-Classical Turkish Style or the National Architectural Renaissance. Later, academics coined the cumbersome term still in use today: the First National Architectural Movement, indicating that a so-called Second National Architectural Movement would later emerge in Turkey, albeit with considerably less success.

The founders of this movement were architects Kemalettin Bey, educated in Berlin, and Vedat Tek, educated in Paris. Among their followers, Arif Hikmet Koyunoğlu and Giulio Mongeri stood out. Their productivity during the 1920s was astonishing, with their works dominating the skylines of major Turkish cities. While these buildings are harder to spot in Istanbul’s rich architectural tapestry of intriguing structures from various eras, in Ankara, these very buildings define the character of the newly established city centre.

Notable among these Ankara landmarks are the Ankara Palas hotel for parliamentarians (1927, begun by Vedat Tek, completed by Kemalettin Bey), Gazi University (1926, Kemalettin Bey), the Ethnographic Museum (1930, Koyunoğlu), and the Museum of Painting and Sculpture (1927, Koyunoğlu). Most iconic, however, is Giulio Mongeri’s Ziraat Bank Headquarters, widely regarded in Turkey as the quintessential and most successful embodiment of this architectural style.

The History of Ziraat Bank

Ziraat Bank (Agricultural Bank) was established in 1863 in Pirot by Midhat Pasha, then the governor of Niš, to help local farmers overcome financial difficulties. Considering the bank’s current financial power, it is the largest company ever founded on Serbian soil. The establishment of this bank was one of Midhat Pasha’s first successful pro-Western initiatives. A forerunner of Atatürk in many respects, Midhat Pasha later built a distinguished political career as a leading reformer and modernizer of the Ottoman Empire, earning great acclaim in Europe. Inevitably, when the political winds in the Empire shifted toward conservatism, his premature progressivism cost him his life – a fate befitting a true Ottoman Pasha.

While the bank was generally successful, its survival was often threatened by the Empire’s chronic political instability. The bank followed the fortunes of a country in decline, frequently relocating its headquarters to safer regions. By 1888, its head office was established in Istanbul. However, during Atatürk’s War of Independence (1919–1923), its branches in Istanbul and Izmir came under occupation. The Izmir branch, then controlled by the Greeks, financially supported the Greek insurgents. In response, a new headquarters was established in Ankara, which became a vital financial backer of Atatürk’s forces.

Following Turkey’s military success, the bank was reunified, and its new headquarters was designated in the most attractive location in Ankara at the time, in the Ulus district. This area was soon to become the centre of government institutions and banks, where the most significant buildings of the newly formed architectural style would be constructed.

Giulio Mongeri

The design of the bank’s headquarters was entrusted to Giulio Mongeri, the most prominent representative of the Turkish national architectural style. Don’t be surprised by his distinctly Italian name and surname; he belonged to a unique, now practically extinct, ethnic community. Mongeri was part of the Italo-Levantines, descendants of Genoese and Venetian traders who settled in the region during the late Byzantine period. Like the Franco-Levantines, who traced their roots to the defeated Crusader kingdoms, they embraced the customs and attire of their oriental neighbours, which lent them a distinctive charm. Yet, they preserved their national and cultural identity and their spoken language – a creole blend of archaic Italian mixed with local Greek and Turkish dialects – the lingua franca in its truest, original sense. Most Levantines were Catholic, though, intriguingly, some were Jewish. They lived primarily in the cosmopolitan cities of Izmir and Istanbul, where they made significant contributions to Ottoman and early Republican Turkish culture.

Giulio Mongeri was born in 1873 into a Catholic Levantine family in Istanbul. His first major work was the unmissable neo-Gothic Catholic Church of St. Anthony on Istanbul’s Grande Rue de Péra (now Istiklal Avenue), completed in 1912. His most prolific period, however, came in the 1920s, when he embraced the Turkish National Architectural Movement and designed a series of notable public and commercial buildings. In Istanbul, Mongeri’s most remarkable works include the magnificent Karaköy Palas (1920) and Maçka Palas (1922). Later, he also designed the pedestal for the Republic Monument in Taksim Square.

However, his most significant contributions can be found in Ankara’s Ulus district, where his buildings defined the character of Turkey’s new capital during the early years of the national revival.

These include the Monopoly Building (1928) and the headquarters of three leading banks: İş Bank (1928), Osmanli Bank(1926), and Ziraat Bank (1926–1929) – the focus of this text.

Ziraat Bank in Ankara – the Architecture of National Revival

I believe many of our architects can and will understand why their Turkish counterparts in the early years of the Republic were reluctant to express themselves too freely in architectural design. The range of acceptable architectural motifs was highly limited. “This can’t be used, because it’s too Greek,” “That’s off-limits, as it’s Persian or Arab,” “This is Islamic, and doesn’t align with the leader’s atheism,” “And that is Western, so it might seem like flattery.” Since even the classic Ottoman, “sultanic” architectural motifs were deemed politically incorrect, the best solution was to find suitable elements from Seljuk traditions – provided there was enough to draw on.

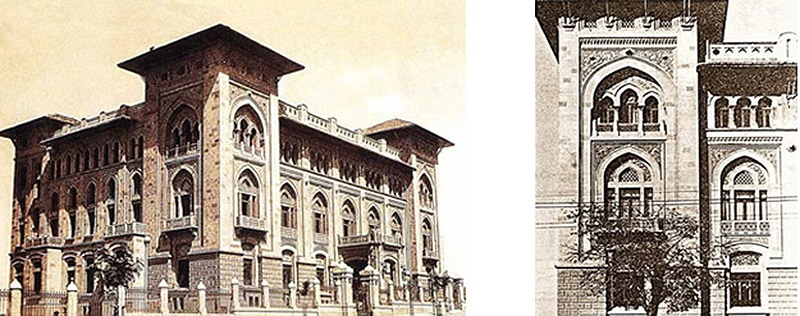

As a result, the architects of the Turkish National Architectural Movement were left with a narrow palette of “approved” motifs, which they creatively recycled across their projects. The Ziraat Bank Headquarters, officially titled the Main Directorate of Ziraat Bank, exemplifies this approach. The building incorporates nearly all the key elements that define the Turkish National Architectural Style.

Given all this, we must admit that the architect skilfully overcame these challenges, crafting a façade that is both harmonious and engaging. The windows with pointed arches – a hallmark of all buildings from the Turkish National Movement – may feel Gothic to us, but they are not of European origin. These forms genuinely appear in old Seljuk structures. On this particular building, the architect breathed new life into the motif by grouping several windows under a single arch, reminiscent of techniques seen in the European Renaissance, and incorporating intriguing multi-tiered recesses that add depth to the façade.

The delicate ornamental details above the windows and around the pointed arches are distinctly Oriental, striking a pleasing balance with the smooth surfaces of the façade. From today’s perspective, if we were to critique anything, it would be the uniform, somewhat monotonous sand-colour of the façade and the bizarrely oversized eaves on the corner towers, supported by angled brackets – a motif borrowed directly from traditional Turkish vernacular architecture.

Time flies. A century has passed, and viziers, Levantines, fezzes, and dervishes now seem as if they never existed. The dilemmas that surrounded the formation of the Turkish National Style are long forgotten. A hundred years after its deepest nadir, Turkey is once again an economic powerhouse, with Istanbul back in the spotlight. Next to it, the world’s largest airport is under construction, and within the city itself, a massive international financial centre is taking shape, dominated by two striking, hypermodern glass towers over 40 storeys high, built in the international style. The towers will become the new headquarters of Ziraat Bank, a powerful financial institution with roots so modest that almost no one remembers it was founded in the depths of rural Serbia. The bank’s management will soon relocate to the new skyscraper, where they will continue to steer millions from their state-of-the-art offices. Meanwhile, the ground floor of Mongeri’s historic building in Ankara has already been transformed into a Banking Museum – an unmistakable sign that the building is being quietly retired to a tranquil museum life.

Darko Veselinović , February 2014