Ankara – Ataturk’s city

After the Great War, the last act of disintegration of the Ottoman Empire took place. Once the world’s greatest power was exposed to the merciless dismemberment of its territory. The complete collapse was prevented by the republican army of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, which successfully opposed the imperial power, foreign occupiers and Greek rebels. But it is one thing to win a war, and quite another to face the tragic backwardness of the country that Kemal Ataturk inherited from the Ottoman sultans. It was necessary to start from the beginning. The program of fundamental reforms turned people’s lives upside down. Yesterday, the Sultan’s subjects were given surnames, the right to vote, the Latin alphabet and the Swiss Civil Code, while dervish orders, fezzes, hijabs and Sharia laws were forbidden to them.

Even while the rich cosmopolitan cities in the west of the country were under foreign occupation, Kemal declared Ankara, a remote Anatolian town, the capital of the emerging Republic. The success of fundamental social reforms is most noticeable today on the streets of that city, which has become the showcase of a new, proud Turkey. A remote kasaba became a world metropolis, the number of inhabitants grew from thirty thousand to around five million, winding alleys became wide boulevards, and corner shops grew into endless rows of luxurious office buildings, car dealerships and shopping malls.

The first national architectural movement

At the very beginning of that process, a small group of architects was ready to take advantage of the favorable moment and offer the new government an already formed instant style solution that would successfully fit into the program of national revival. At the time of the formation of the Republic, the process of creating that particular style had already lasted for at least 10-15 years, and political difficulties played an important role in its formation. As first the Christian and then the Muslim nations separated from the Empire, the new Turkish architecture was in constant self-correction and in its final form reflected primarily Turkish, not general Islamic, nor supranational “Ottoman” values. In addition, it had to make a departure from the classical Ottoman architecture, now considered reactionary, and by emulating successful Western countries to emphasize modern trends, but also to avoid humble imitation of the West. Despite all these ideological challenges, a few Turkish architects, passing between Scylla and Charybdis, successfully built Western buildings with oriental decoration, national, but not Islamic in character. Contemporaries spoke of their style as a neoclassical Turkish style or as a national architectural renaissance, but later in academic circles a rough expression was coined that is still used today: The First National Architectural Movement, which indicates that in a later period it will be relevant in Turkey , and the much less successful, so-called Second Architectural National Movement.

The founders of the movement are the architects Kemalettin Bey, educated in Berlin, and Vedat Tek, educated in Paris, and among those who joined them, the most outstanding were Arif Hikmet Koyunoglu and Giulio Mongeri. The pace of their work in the twenties was amazing, so their facilities flooded the big Turkish cities. Admittedly, in Istanbul, among the multitude of interesting buildings from all periods, it is difficult to notice them at first glance, but in Ankara, it is these buildings that give character to the newly formed city center. Among those Ankara buildings, the Ankara Palace Hotel for Members of Parliament (1927, started by Vedat Tek, continued by Kemalettin Bey), Gazi University (1926, Kemalettin Bey), Ethnographic Museum (1930, Koyunoglu), Museum of Painting and Sculpture (1927, Koyunoglu) stand out. , and especially Mongeri’s buildings, of which the Ziraat Bank headquarters building, which in Turkey is considered the most typical and successful representative of the style, attracts special attention.

History of Ziraat Bank

The Ziraat (agricultural) bank was founded in Pirot by the then governor of Niš, Midhat Pasha, in 1863 to help local peasants overcome financial difficulties. Considering today’s financial power of that bank, it is the largest company ever founded on the territory of Serbia. The establishment of this bank is one of the first successful pro-Western moves of Midhad Pasha, a kind of Ataturk’s predecessor, who later made a rich political career as a leading reformer and modernizer of the empire and thanks to this enjoyed a great reputation in Europe. Of course, on the first occasion when more conservative political winds blew again in the Empire, he paid for his premature progressiveness with his head, as befits a true Turkish Pasha.

Although the bank was generally successful, its survival in the later period was often threatened by constant political instability. The bank followed the fate of the crumbling country, so the head office was moved several times to safer areas. Since 1888, the bank’s head office has been in Istanbul, but during Ataturk’s War of Independence in 1919-1923, the branches in Istanbul and Izmir came under occupation. The Izmir branch, then under Greek control, financially supported the Greek rebels, so a new bank headquarters was established in Ankara, which, in turn, provided financial support to Ataturk’s army. After the Turkish military success, the bank was reunited and the most attractive location in Ankara at that time, in the Ulus district, which will soon become the seat of state institutions and banks and where the most significant buildings of the newly formed architectural style will be built, was determined for the new headquarters.

Giulio Mongeri

The most prominent representative of the Turkish national style, architect Giulio Mongeri, was selected as the designer of the headquarters of this bank. Don’t be surprised by his Italian name, because he was a member of an unusual, now practically extinct ethnic community. He belonged to the Italo-Levantines, descendants of Genoese and Venetian merchants who had settled on this land since the late Byzantine period. They, like the Franco-Levantines, who have their origins in the defeated Crusader kingdoms, received the customs and way of dressing of their oriental neighbors, which gave them a special charm, but they preserved their national distinctiveness and spoken language, a creole mixture of archaic Italian with local Greek and Turkish languages – a lingua franca in its basic, original meaning. Most of the Levantines were Catholic, although, curiously, some of them were of the Jewish faith. They lived primarily in the cosmopolitan cities of Izmir and Istanbul, and from there contributed significantly to Ottoman and early republican Turkish culture.

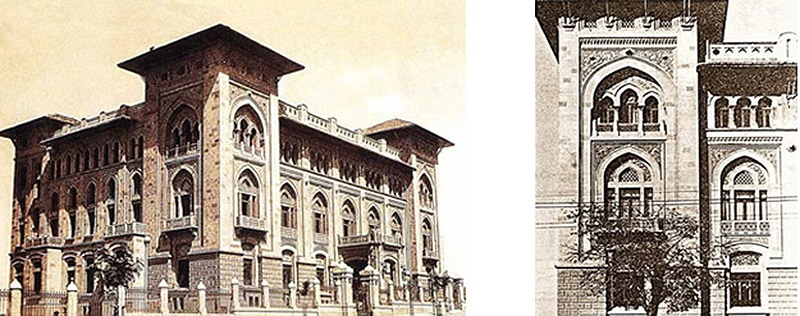

Giulio Mongeri was born into a Catholic Levantine family in Istanbul in 1873. His first significant building was the indispensable Neo-Gothic Catholic Church of St. Antoine in Istanbul’s Grande Rue de Péra (now Istiklal Avenue) from 1912, and was most prolific in the 1920s when he aligned himself with the Turkish national architectural movement and designed a series of significant public and commercial buildings. In Istanbul, the magnificent palaces stand out: Karakoy Palace (1920) and Mačka Palace (1922), and later he also designed the pedestal of the monument to the Republic on Taksim Square.

However, the most significant are his buildings in Ankara’s Ulus district, which in the first years of the national renaissance gave character to the capital of the new Turkey.

These are the Monopol building (1928) and the headquarters of three leading banks: Is Bank (1928), Osmanli Bank (1926) and Ziraat Bank (1926-1929), the building that is the subject of this text.

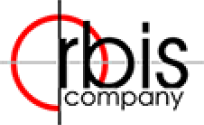

Ziraat Bank in Ankara – Architecture of National Revival

I think that many of our architects will understand well why their Turkish counterparts in the first years of the Republic were not allowed to expand much in architectural expression. Desirable architectural motifs were very limited. You can’t do this, because it’s too Greek, and you can’t do that, because it’s Persian or Arabic. Well, this is Islamic, so it’s not very close to the leader’s atheism, and it’s Western, so it will turn out that we are investing in them. As the classic Ottoman, “sultan” architectural motifs were not politically correct, it would be best to find some nice features from the Seljuk tradition, if that would be enough…

All in all, the leading representatives of the Turkish national architectural movement had at their disposal a very limited number of “allowed” motifs, so they recycled and used them on almost all buildings. Thus, on the building of the Main Directorate of Ziraat Bank, as it is officially called, we can see almost all the architectural motifs that characterize the Turkish national architectural style.

With all that in mind, we have to admit that the architect did a great job and made the facade harmonious and interesting. Windows with broken arches, a mandatory motif on all the buildings of the Turkish national movement, which we feel are Gothic, are actually not of European origin and indeed appear on old Seljuk buildings. Especially on this building, the architect breathed new life into that motif by grouping and placing several of them under one arch, as was done in the European Renaissance, and by interesting multi-level indentation in relation to the plane of the facade. The filigree decorations above the windows around the broken arches are typically oriental and are in beautiful balance with the smooth parts of the facade. If we criticize the building from today’s perspective, then it is the monotonous, boring color of the sand and the bizarrely large eaves on the corner towers supported by eaves, which is a template transferred motif from Turkish folk architecture.

Time flies. Only a hundred years have passed, and viziers, Levantines, fez, dervishes… it’s as if they never existed. The dilemmas that accompanied the formation of the Turkish national style no longer interest anyone. One hundred years after the deepest abyss, Turkey is once again an economic superpower, and Istanbul is once again in the center of attention. The world’s largest airport is being built next to it, and a large international financial center is emerging in the city itself, which will be dominated by two attractive hypermodern glass towers of over 40 floors in an international style. It will be the new General Directorate of Ziraat Bank, a powerful financial institution that, although no one remembers it anymore, was born shyly in the depths of rural Serbia. The management of the bank will move to the new building to turn over millions from there, and on the ground floor of the old one, Mongeri’s building in Ankara, the Museum of Banking has already been opened as a precaution, which is a clear sign of the departure of this object into a peaceful museum retirement.